The Famicom: more than just a game console

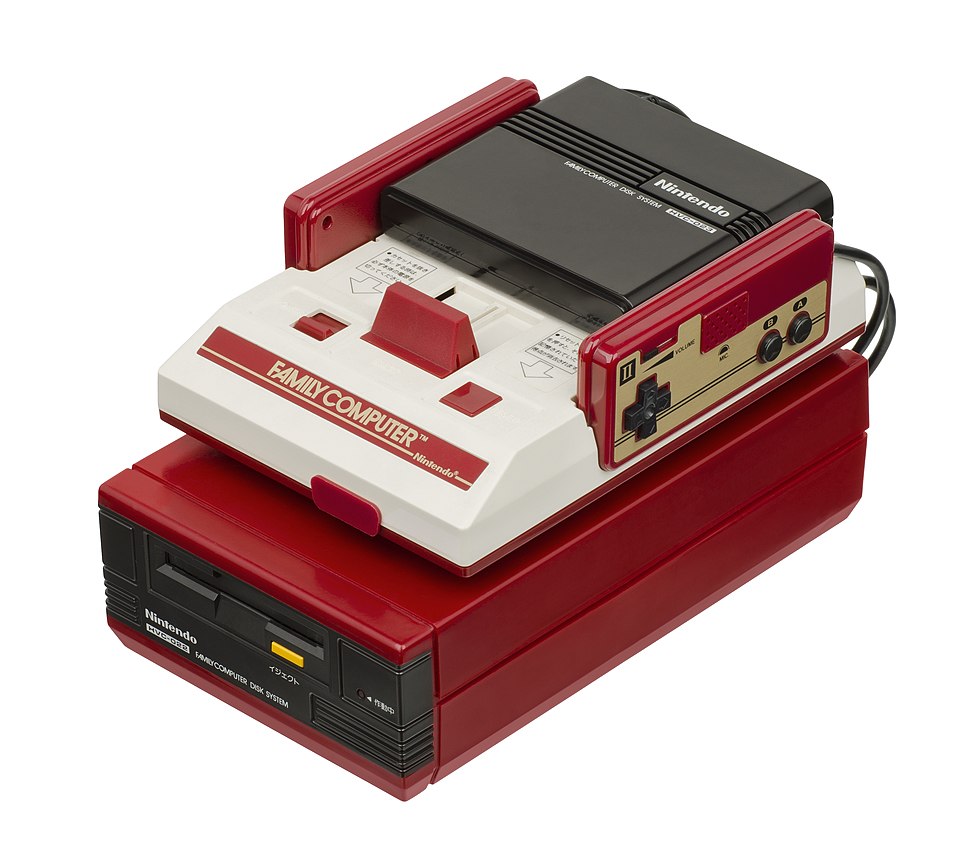

A picture of the legendary Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES.

Ever since the release of the Steam Deck, which allows you to play PC games on a handheld game console, the distinction between a game console and PC has been significantly blurred. But what if I told you that all the way back in the 1980s, the difference between a PC and game console was already becoming indistinguishable, and that the console we got in the West as the NES was supposed to be a general-purpose computer?

The Famicom: a Family Computer

While Nintendo had previously flirted with video games with the Color TV-Game, home consoles that could only play one game each, Nintendo really became a household name with the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), a system originally released in 1983 as the Family Computer, or Famicom in Japan.

The original Family Computer, or Famicom. The NES that we got in the West was redesigned to resemble a VCR and came with a robot, to distance itself from game consoles after the American Video Game Crash of 1983.

The name Family Computer alludes to the fact that it was originally envisioned as a computer masquerading as a toy by Nintendo’s late president, Hiroshi Yamauchi. This would make the Famicom less intimidating than a PC and would be something even kids could have fun with. He appointed Masayuki Uemura as head of Nintendo R&D2, the new hardware division of the company, to design what would become the Famicom.

Since the Famicom was intended to be useful as a general-purpose computer, part of its basic design was a chip that would allow peripherals to talk directly to the CPU― anything from keyboards, to modems, to disk drives.

“It was why the machine would later be called Yamauchi’s Trojan Horse: It slipped into living rooms with nothing but a pair of controllers, innocently toylike, yet it included the capability to do far more than play games.”

― From Game Over, Press Start to Continue: How Nintendo Conquered the World (p. 34)

Famicom addons

Sure enough in 1984, a year after its release, consumers got Family BASIC, which let anyone program the Famicom using its dialect of the BASIC programming language. It included a keyboard that connected to the expansion port in front of the console to make programming easier.

Out of the box, it came included with a few programs: Calculation Board, a calculator, Music Board, a music sequencer, and Message Board, for writing notes. A nearly identical version of Family BASIC, called Playbox BASIC, released for the Sharp C1 TV-plus-Famicom combo system, comes with Biorhythm Board instead of Message Board.

Biorhythm Board tried to predict fluctuations in your physiological, emotional, and intellectual state using psuedoscientific biorhythms. Other than replacing Message Board, Playbox BASIC was otherwise identical to Family BASIC.

Image source: Playbox BASIC vs. Famicom BASIC comparison page (in Japanese)

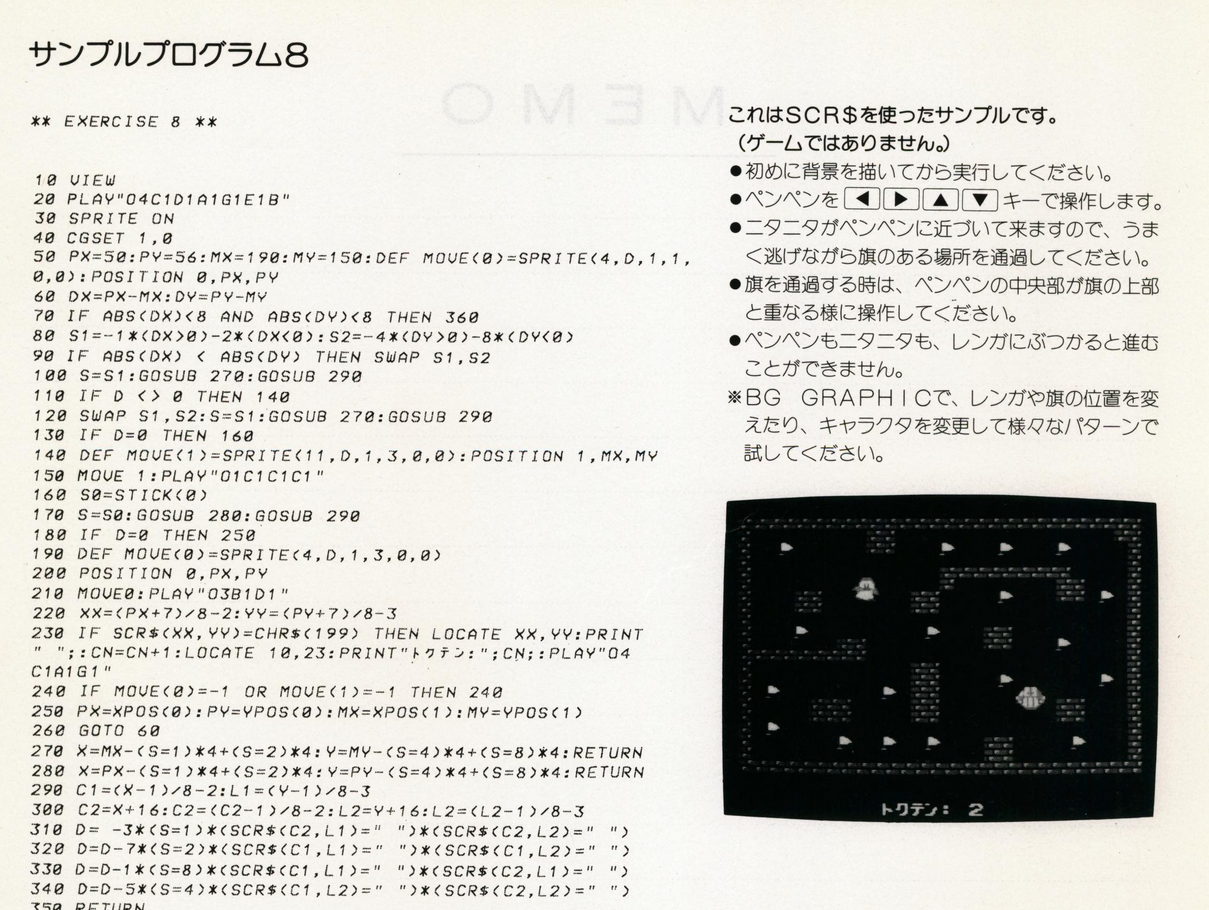

It also had a manual that showed you how to make eight different sample games with BASIC, including Route 66, a top-down driving game, Type Master, a typing game, and Sample Program 8, which the manual insists is just a tech demo, not a game.

Sprites were provided with Family BASIC that you could use in your own programs. Image source: Mario Wiki

Sample Program 8 is a turn-based… “non-game.” The player moves Penpen, then Nitanita moves to catch him. You get points by moving Penpen onto the flags.

Image source: Screenshot from Mikasen’s Family BASIC sample program showcase video

Page 101 of the Family BASIC 2.1 manual, showing the code for Sample Program 8. In the top right, it says ゲームではありません, translating to “This is not a game.”

For Penpen, this is a matter of life or death.

Many third-party games and programs made in Family BASIC were distributed in books and magazines like Program Pochette, Micom Basic and many more. Like the examples in the Family BASIC manual, these were lines of source code that you would have to type into your Famicom manually in order to run.

While typing the full code to a program may seem tedious to us today, this was a fairly common way to distribute programs at the time, including for the best selling desktop computer of all time, the Commodore 64.

Although most of the examples focused on games, Family BASIC was a complete

programming language, so you could make anything you wanted. If you knew how the

hardware worked (or were patient enough to figure it out), you could even unlock

the Famicom’s full power by calling low-level CPU instructions with the CALL

function.

Alongside Family BASIC, you could also buy the Famicom Data Recorder, to save your programs to a cassette tape. This was identical to a normal tape deck, on which you would hook up the microphone and speaker ports to corresponding ports on the Famicom Keyboard.

The Famicom Data Recorder is cassette deck that says Nintendo on it. Other than printed source code, cassettes were another popular way to share programs on home computers, Commodore 64 included.

It wasn’t until the release of the Famicom Disk System that the Famicom could use floppy disks. Rather than normal floppy disks however, Nintendo came out with a proprietary disk format called the Disk Card, which slotted into the disk drive part of the addon.

The Famicom Disk System addon consists of two parts connected by a cable: The disk drive where you insert Disk Cards (bottom), and a RAM adapter which slots into the Famicom cartridge slot (top).

Since the Famicom Disk System occupied the cartridge slot used by Family BASIC, there was no officially supported way to save BASIC programs to a Disk Card. It took until the year official support ended for the Famicom Disk System in 2007 that Japanese console modders found a way to do so.

The main use of a Disk Card was to take it to Disk Writer kiosks at game stores where, for just ¥500 (~US$4.46 in 2025), you could overwrite it with a new game from Nintendo. With disks being cheaper than Famicom cartridge games, and with game cartridge rental becoming functionally illegal with the Japan Copyright Act of 1984, the Famicom Disk System managed to sell 4.4 million units before it sales ended in 1993.

A Disk Writer kiosk. Image source: Nintendo (in Japanese)

Certain Disk Writer kiosks were also fax enabled. Some Disk Card games would write your scores to the disk, and you would take it to one of these Disk Fax kiosks to fax your scores to Nintendo, allowing you to participate in a nationwide leaderboard. It’s a bit of a stretch, but you could arguably call this Nintendo’s first “online gaming” service.

Famicom Network System

Yamauchi was a staunch believer in Nintendo as more than just a game company― he wanted his company to be a key player in the upcoming Information Age. In a speech given to his employees, he proclaimed:

“From now on, our purpose is not only to develop new exciting entertainment software but to provide information that can be efficiently used in each household.” Translation from Game Over, Press Start to Continue: How Nintendo Conquered the World, p. 77.

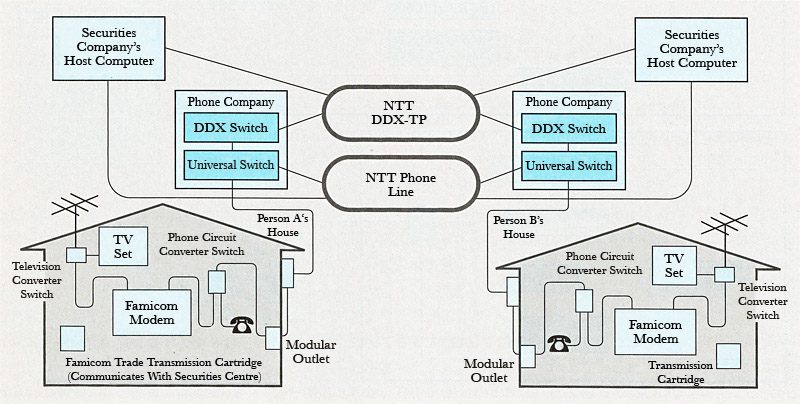

The keystone to this vision was the Famicom Network System, developed in cooperation with Nomura Securities, a stock brokering company. Nintendo would build a modem for the Famicom, and Nomura Securities would build a database that could be reached using the modem to access up-to-date stock market data.

Like dial-up internet, the Famicom Modem used a phone line to connect Famicoms to services on the network. Data would be encoded as sound and travel through the telephone line, and finally decoded back into data by the modem.

Image source: Developing the Famicom Modem in Nikkei Electronics, translated by GlitterberriAccording to Uemura Masayuki, Nintendo R&D2 “wasn’t confident that they would be able to make network games entertaining,” but with Nomura Securities handling development of the database, Nintendo figured that the infrastructure would already be in place and they could figure out making online games fun later. Ultimately, this meant that few games were actually released for the Famicom Network System aside from Konami’s Tsuushin Shogi Club.

Instead, the Famicom Network System launched with exciting titles like Nomura no Famicom Trade, which allowed you to trade on the stock market. You would insert the Tsuushin Cartridge (“Communication Cartridge”) into the modem, and with the number pad on the Famicom Network System’s special controller, you could choose which stocks you wanted and in what quantity.

A Famicom Network System controller with numpad. Image source: raphnet.net

Copies of Nomura no Famicom Trade, as well as programs for other stock brokers can be seen in this picture. The box featuring Doraemon is Sumitomo Homeline, a program for doing your home banking with Sumitomo Bank.

Image source: famicom.suppa.jp (in Japanese)The most popular use of the Famicom Network System was gambling on horse races with JRA-PAT, or JRA Personal Access Terminal, developed by the Japan Racing Association. It was so successful that it captured 35% of the Japanese horse betting market, competing with PCs and dedicated betting terminals.

Unfortunately, much of the software released to use the Famicom Network System has become lost media since the network was taken down. For instance, there are Japanese newspapers mentioning Post Transfer Home Service for dealing with the post office, Cattleya AV Club for buying CDs, and a program for buying clothes, but the whereabouts of these cartridges are unknown.

This news article tells of upcoming programs that would let you buy train tickets, do online shopping, and make hotel reservations all from your very own Famicom.

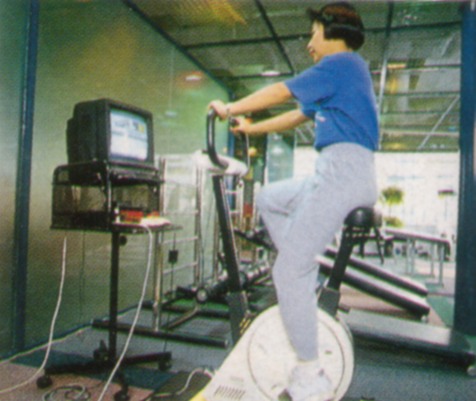

Image source: JDMA News, 1989 November 15 (in Japanese)There’s also the Famicom Fitness System, developed jointly with Fukuoka University and a few other companies, that allowed the Famicom to read data from an exercise bike. It was marketed to fitness gyms and medical institutions, and was scheduled to be marketed to the general public in December 1990, but it is unknown if this ever happened.

With an exercise bike connected, you could then enter your weight and age, and pedal for 12 minutes. After uploading your pedalling data, you would receive a personalized exercise regimen.

Image source: famicom.suppa.jpWhat eventually killed the Famicom Network System was the onset of the Lost Decades, a period of nationwide economic stagnation, starting in the early 90s. With stock trading comprising much the Famicom Network’s traffic, consumers’ plummeting interest in stocks was the final nail in the coffin for a service that was already difficult to set up and use.

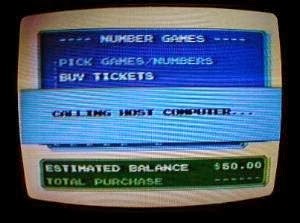

In the West, Nintendo hoped to create a similar network to the Famicom Network System in the United States with partners like AT&T and Fidelity Investments, but the idea came under fire when a program to play the Minnesota State Lottery was announced. Concerns over underage gambling were raised, and the NES modem was killed before making it to market.

If Nintendo of America hadn’t started with the Minnesota State Lottery, could we have been online shopping and doing our taxes with an NES?

Image source: The NES CatLegacy

Despite its demise, some of the ideas behind the Famicom Network System were recycled for the Satellaview, a satellite service for the Super Famicom (known as the Super Nintendo in the West). Satellaview allowed users to receive satellite broadcasts to download games, magazines, and other media.

The Super Famicom sits neatly on top of the Satellaview. Like the Famicom Network System, this was also a Japan exclusive. Image source: Muband on Wikipedia

The horse betting program JRA-PAT, being one of the most popular applications, was re-released for the Super Famicom. As time marched on, internet connectivity became the norm with consoles like the Sega Dreamcast, which had an inbuilt modem and yet another re-release of JRA-PAT that had excellent music.

Nowadays, we often take both our PCs and the internet for granted. Everywhere we go, we are constantly connected to services that let us do everything the Famicom could do and more. But for a time, not every home had a PC. You might just have a TV, a landline telephone, and a Famicom that was more than meets the eye.

Your game consoles are so much more

Even though Nintendo no longer designs game consoles to be general-purpose computers, most game consoles nowadays are essentially PCs with specialized gaming hardware.

The original Xbox (short for DirectX Box), is really just an x86 Intel Pentium PC with a customized version of Windows for gaming.

Linux on the Playstation 2 and 3 were officially supported by Sony with PS2 Linux and OtherOS. This was such a useful feature that researchers built compute clusters using PS3s to speed up black hole simulations, cryptography research, and analyzing satellite imagery. When Sony removed the OtherOS feature in 2010, a class-action lawsuit was brought against them, proving that people really did care about Linux on their game consoles.

The PS3 Gravity Grid was a cluster of 400+ PS3s built by Dr. Guarav Khanna to study black holes. Image source: University of Rhode Island

The Nintendo Switch is an ARM-based computer capable of dual-booting into Linux and Android with Switchroot. Using Linux on the Switch is great because you can carry it around to do most things you’d do with a PC, and it even comes with a convenient dock so you can connect it with a keyboard, mouse, and monitor when you’re at home.

The catch? Nintendo makes it as hard as humanly possible to do so. Developers had to hack the device by shorting two pins on the Joycon connector to gain access the bootloader and install other OSes. When this was publicized, Nintendo changed the hardware so you now need to install a modchip to do so, requiring incredibly precise microsoldering skills.

In our hands, we hold the ghost of Nintendo’s dream: a Nintendo computer in every home that could be your portal to the world’s information. In a way, Nintendo got that wish― it’s just not profitable for them anymore.